The successor to JobKeeper can’t do its job. There’s an urgent need for JobMaker II

Until the end of last month one million workers were paid by JobKeeper.

This month there are none. Treasury thinks up to 150,000 will lose their jobs.

Credible estimates put the number higher, at as much as one quarter of a million.

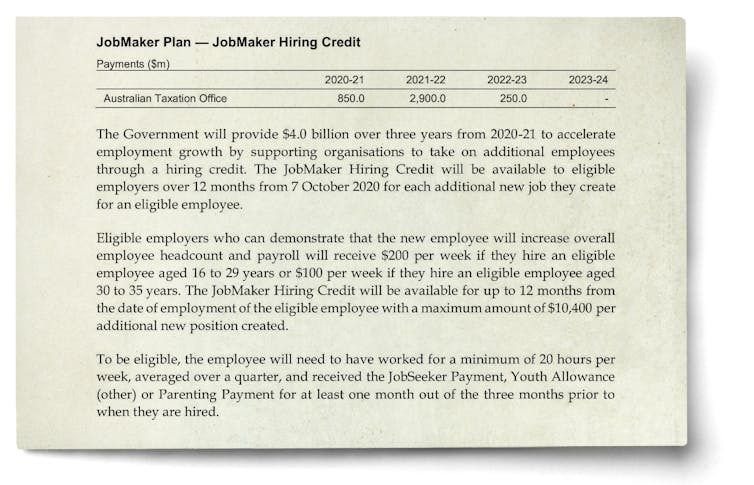

In its place, the government introduced a A$4 billion JobMaker Hiring Credit. It will give employers who can demonstrate that a new employee will increase overall headcount (and payroll) $200 per week if the new hire is aged 16-29, or $100 if the new hire is aged 30-35.

Billions on offer, little takeup

Employers will get nothing for new hires aged 36 and over — no matter how disadvantaged and no matter how suitable.

The scheme hasn’t got off to a good start. It is reported to have had only 609 applications in its first seven weeks.

The October budget said it would attract 450,000 applications, creating 45,000 jobs.

The low takeup isn’t surprising.

Evidence shows when unemployment is high, the best way to target disadvantaged groups (such as young jobseekers) is not to target them, but to target high employment growth more broadly.

High employment growth disproportionately helps less-advantaged workers because they are further down the hiring queue.

The $4 billion appropriated for JobMaker is still available to be spent. If spent well, it would help consolidate what so far has been a very solid recovery.

But it needs to be simplified. JobMaker II could be set up as a tax rebate on the quarterly increase in firms’ payrolls, say 60% on any increment above 6%.

Firms that were on JobKeeper in the March quarter (its final quarter) would be allowed to deduct their JobKeeper receipts from their payroll in estimating the starting point for the calculation.

JobMaker II could save 100,000 jobs

If those firms retained their workers (and the rebate was set at 60% on any increase in payroll beyond 6%) they would receive a little over half their March quarter JobKeeper payment in the June quarter.

Most of the money would go to firms and disadvantaged workers who still need it.

The ordinary job matching process would be allowed to work, without some jobseekers being given preference over others because of factors such as their age.

And firms already thriving would have an incentive to increase their employment by even more.

But it should be announced this week

The proposal would have to be implemented quickly to maintain the momentum established by JobKeeper. With JobMaker as it is, it will slip away.

The main thing required is for the treasurer to make an announcement setting out the broad outlines.

The week after Easter is a time when business owners will be taking stock – working out whether they can afford to continue to carry workers who until the end of March were supported by JobKeeper.

Our modelling suggests that refashioning JobMaker along the lines we have suggested could save and generate 100,000 to 130,000 jobs over the next six months.

It would keep employment 1% higher than it would have been, generating higher wage growth and higher tax revenue leading to a lower budget deficit.

With interest rates close to zero, the employment effect would be sustained.

The impacts would be greatest for young and for low-skilled workers, with the bulk of the benefits flowing to wages rather than profits (as regrettably happened in high profile cases as a result of JobKeeper).

And without the discrimination implicit in age targeting, other genuinely disadvantaged groups, including low-income women over 35, would be better off.

Those women would be in a better position to build their superannuation balances and be less exposed to homelessness.

The economy seems on track for a rapid recovery. But with the pandemic continuing and the outlook uncertain, it’d be wise to take out insurance.

With interest rates low, even a more expensive JobMaker II would pay for itself.![]()

Renee Fry-McKibbin, Professor of Economics, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University; Peter M. Downes, Research Associate, Centre for Climate and Energy Policy, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University, and Warwick J. McKibbin, Chair in Public Policy, ANU Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis (CAMA), Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AccomNews is not affiliated with any government agency, body or political party. We are an independently owned, family-operated magazine.